As is custom, the start of a new year in Ethiopia is accompanied by wishes for peace, happiness, and prosperity from friends, relatives, neighbors, and even strangers. And while these wishes may help get the new year off to an upbeat and optimistic start, they have not come true very often in recent times. The just-ended 2017, though it had its highlights, brought with it more conflict, instability, financial distress, and political uncertainty.

Ethiopians everywhere hope 2018 will be the year when well-wishers are proved right, when problems inherited from the past are set right, and when the country climbs to new heights.

The Reporter’s Nardos Yoseph spoke about the prospects of the new year and the highlights of the old with a few well-known political figures and analysts. This is what they had to say:

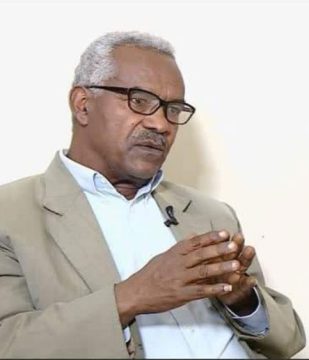

The Reporter: How would you assess the past Ethiopian year?

Mulatu Gemechu: As you know, the year was very challenging. There was war, insecurity, and a situation where people could not freely move from place to place. It was a very difficult year. Our hope is that 2018 will be different, that peace will prevail, and that people can once again move about safely, that the bad will pass and the good will come.

Were there any significant positive or negative developments during the year?

To be honest, there was nothing we could call a positive development for us. It was a difficult year. As you know, our party’s offices were closed, our movement was restricted, and we were unable to present our political program, our social policies, and our economic agenda to the public. It was a year in which we were unable to do what we are supposed to do. So, no — we cannot say there was any success.

What are your expectations for the new year?

We believe the upcoming election can only be conducted if there is peace. Peace must come first. People need to feel safe, move freely from place to place, and express themselves without fear. Democracy must be given space, and democratic institutions must be strengthened so that a conducive atmosphere for elections can be created. If this happens, we believe there can be a credible election in which the public can freely choose their representatives. Otherwise, if an election is simply declared for the sake of it, then it becomes a business-as-usual exercise — which we do not support.

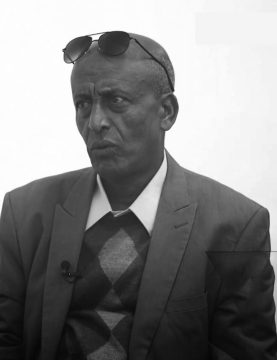

The Reporter: How would you assess the past Ethiopian year?

Berhane Atsbeha; For the people of Tigray, for its politicians, and for society as a whole, the past year was very bitter. It was a year of despair, a year of frustration, a year in which hopes were dashed and expectations were broken. It was not a year of complete loss of hope, but it was a year filled with pain.

Politically, it was the year when the first Interim Administration came to an end and a new Interim Administration was formed. It was a year when a forced restructuring of power took place. It was a year that left behind unsettled questions. It was also a year when society and political forces alike experienced disappointment and betrayal.

Economically, it was a year of collapse. Even though the sound of bullets has lessened, the economic destruction has continued. Inflation has worsened, scarcity has deepened, unemployment has spread, and people are burdened by debt. Our youth, as a result, were forced to migrate, and many paid with their lives — in Djibouti, in Saudi Arabia, and across dangerous seas.

Socially, it was a year of trauma. Families remain in grief. The suffering caused by the war is still very fresh. The questions of prisoners, the disappeared and displaced people have not been resolved.

In terms of peace, it was a year that fluctuated between light and shadow. At times there seemed to be peace, and at other times, the threat of war reappeared. The conflict with Eritrea, especially, has been a constant shadow of fear.

Overall, it was a very painful year — though not completely hopeless.

Were there any significant positive or negative developments during the year?

The year saw the final stages of the initial transitional administration in Tigray. Its inability to fully stabilize the situation affected the life of the Tigrayan population and caused severe economic disruption, even after the war. The year also left additional burdens. The promises of the transitional administration were largely unmet. While the government at the presidential level tried to assert authority, the reality on the ground showed widespread disillusionment. Economic instability persisted, including inflation and rising cost of living. Post-war recovery remained slow, and the Tigrayan youth were forced to leave for neighboring countries such as Djibouti and Saudi Arabia, risking their lives.

Overall, it was a year in which Tigray faced not only political and economic setbacks but also social and psychological strain. The loss of peace and security was felt deeply, and internally, the society remained fragile.

What are your expectations for the new year?

The first responsibility of the people of Tigray in the new year is survival. Existence itself must be the primary goal. To survive in such difficult conditions is in itself a victory.

As SAWET, our first belief is that the people of Tigray must continue to exist. Existence comes before politics. After that, our priority is to safeguard territorial integrity, to restore our economy, and to secure peace.

For 2018, we also hope for an improvement in stability, for the lessening of despair, and for stronger unity. On paper, the National Election Board has a plan. But as SAWET, we do not believe that there is either the capacity or the conditions in Tigray to conduct elections. The Interim Administration itself does not have much time left to make such preparations. Therefore, we do not think that elections are realistic at this time. There are attempts to create internal divisions and to fuel conflict. The risk of internal strife is real.

But our stance is that political forces should resolve their differences through dialogue rather than bullets. If that does not happen, it will be the youth who pay the price first.

Our hope is that 2018 will be a year when guns fall silent and dialogue prevails.

The Reporter: How would you assess the past Ethiopian year?

Girma Bekele: Well, in general, the Ethiopian year 2017 was one in which we hoped to see many of the country’s problems addressed. At the start of 2017, we expressed our wish that it would be a year of national consensus and reconciliation, where all of us, with our diverse ideas, could come together to create a situation that would bring peace to our country and lay the foundation for sustainable development. But unfortunately, this was not realized to the extent we had hoped.

Instead, civil war-like conflicts have persisted in the country and undermined our hopes. It is saddening that instead of seeing progress in development and good governance, what we faced was a worsening of challenges.

Were there any significant positive or negative developments during the year?

On the negative side, democracy-building has been hindered. We witnessed the exile and imprisonment of journalists and many others. The repression of free democratic institutions, the weakening of human rights organizations and the inability of the government to allow independent institutions to operate freely and independently are very concerning. These are negative developments that must be underlined.

On the positive side, however, the situation around the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) stands out. Though there are questions and debates around it, this project is something that we must support without reservation. It is a second Adwa, a second victory. At the time, we repelled the enemy that came with arms to invade our land; now, through this project, we are reversing Ethiopia’s image as a symbol of famine. GERD is a powerful instrument for national development, boosting our energy supply, strengthening our foreign currency reserves, and above all, playing a transformative role in our agricultural economy. It also opens opportunities for better relations with neighboring countries (aside from historical adversaries). For these reasons, we consider it a major positive achievement of the year.

What are your expectations for the new year?

The year 2018 is expected to be an election year. At the same time, many economic questions remain unresolved. So what should we expect? What kind of work lies ahead?

For our party, national consensus and reconciliation are not temporary slogans but part of our political program. Ethiopia is home to more than 85 nations and nationalities, and naturally, diverse social, economic, and political questions will always arise. These need to be addressed around the table. Questions of identity may emerge, as well as questions of economic justice, language, and culture. These must be discussed openly, and institutions that allow the people to express themselves must be strengthened.

Looking at the country today, even beyond politics, we see open tensions in Oromia, Amhara, and Tigray. There is high unrest. In Gambella, Benishangul-Gumuz, as well as between Somali and Afar, we see conflicts and intensifying tensions. We are not in a situation where we can say there is peace with any region, or that we can continue development in a stable manner. If this is not addressed in 2018, then we will continue to live under empty propaganda, lies, loud rhetoric, and false promises of prosperity, while the political space shrinks and the government monopolizes power.

That is why we must urgently push for national consensus. We will continue our efforts in this regard. Political forces across Ethiopia, whether from ruling or opposition parties, must cooperate and come together. Likewise, other stakeholders in Ethiopia’s future must also participate in this collective effort.

This year should be the time when we make the real effort to rescue our country from collapse and chaos. For our part, we will make every contribution possible to ensure this.

The Reporter: How would you assess the past Ethiopian year?

Costantinos BerhuTesfa : It was a year in which many reforms were carried out in the economy. First, after fifty years, new policy shifts were introduced including laying the legal ground that allows foreign banks entry, reforms in the forex trade, and strengthening of Ethiopian Investment Holdings, which consolidated state-owned enterprises under one umbrella. We also saw the launch of the capital market, which previously was just an idea about a future stock exchange. These were significant policy reforms. I believe these measures could have a profound impact on major economic issues in the years to come.

Were there any significant positive or negative developments during the year?

On the positive side, in 2017, the government improved tax collection. We also witnessed an increase in state revenue. The central bank recorded good outcomes in various exports, especially gold and coffee. These were encouraging results.

On the negative side, however, such policy shifts come with macroeconomic challenges. For instance, the volatility in the market has directly affected ordinary people. Imported goods such as sugar, edible oil, and other consumables became much more expensive. People already burdened with debt are now struggling more because of rising living costs and the shortage of foreign currency.

Even though the government claims inflation has been reduced from more than 30 percent to 14 percent, the cost of living crisis continues to seriously impact the population. These issues, in my view, require urgent government response.

What are your expectations for the new year?

Looking ahead to 2018, I believe there is hope for improvements in the economy if certain issues are addressed. The first is governance: the government must improve its performance in good governance, which has been identified as a major bottleneck. If tackled properly, this would be very promising.

The second challenge is contraband and illicit trade, which are draining the economy. I expect improvements on this front. Closely linked to this is the issue of illicit financial flows. The Washington-based Global Financial Integrity reported that Ethiopia loses up to USD 3.5 billion annually through illicit financial transfers. Africa as a whole loses USD 88 billion, with Ethiopia being one of the major contributors.

If governance improves, contraband is curbed, and illicit financial flows are controlled, then I believe the economy could show much better growth.

Another promising development is the entry of foreign banks. Since they bring in foreign currency, this could help finance large-scale capital projects, create jobs, and generate opportunities for the youth. At the same time, newly established investment banks could play a critical role. Unlike commercial banks, these institutions would focus on equity financing and shareholding, which could strongly support startups and emerging entrepreneurs.

However, I must emphasize that without peace, economic growth is very difficult. During times of war, wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few companies, while the broader economy suffers. Therefore, peace is essential for Ethiopia’s sustainable economic progress.

But what harms the economy most is this situation we are in now. The government says we are growing by eight percent, but if GDP is really meant to improve people’s livelihoods, then the country’s challenges must be solved. Especially now, indeed, the government has established a National Dialogue Commission, peace committees are being set up, but the question remains: beyond that, what more can be done?

Because if there is no peace in the country — especially in the major regions like Amhara and Oromia, where the problems are very serious — the economy will suffer greatly. And in 2018, along with the completion of the Grand Renaissance Dam, the government must turn its face towards peace and open the way to achieve it, I believe.

If these macroeconomic reforms are followed, Ethiopia could return to growth above 10 percent, as it once had before. And the people, who are now burdened by inflation, low income, and the overall pressure of living costs, could see some relief.

But the government must urgently prioritize four issues: corruption, illicit financial flows, foreign trade, and securing peace. These are matters that are in the government’s hands and can be addressed with urgency.

As for the agricultural sector, perhaps certain works could be carried out to strengthen it. Agriculture is the main driver of the economy. So now, with selling shares of state enterprises and taking various measures, there must be ways to expand participation in the agricultural sector.

Previously, in different ways and under different governments, developing the private sector has always been a mantra. That’s true today, but the problem is that the government itself, through corporations and agencies, is always expanding the state sector. This is very dangerous for the development of the private sector.

The reason is that the government can borrow from its own banks, it can borrow from abroad, it can use the taxes it collects and the aid it receives — it has a lot of money. In addition, there are enterprises tied to the ruling party. All these prevent the private sector from growing.

When Prime Minister Abiy first came to power, he said, “We will address the question of ease of doing business.” And indeed, many things have been done so far — such as opening industrial parks, introducing digital administration, e-government systems, and so on. But still, people continue to complain. When they go to a woreda office or a city office, the situation is such that they cannot get services without bribery.

These things must be corrected by the government. What would make the private sector grow most of all, in my opinion, is the arrival of foreign banks. Because when foreign banks come, foreign investors will also come with them. The reason is that investors believe that if foreign banks are here, they will be able to get financing. And these investors have experience working with such banks.

These foreign private investors can grow the private sector in Ethiopia in a way that could lift it all at once — that is my belief. For this reason, now everything at the woreda administration level is handled atworeda level: education, health, investment, mining, agriculture, infrastructure, and all basic development activities. And even though the people there are elected, those who could support them — such as graduates of Addis Ababa University in development administration or public administration — are not being seen entering government service.

A way must be created for them to work within the government. Because in public administration and development administration, development managers are trained to integrate all the development actors and bring growth at the end. And most of the woreda administrators who come through elections often lack such skills. They might manage politics, but they cannot implement development programs, control corruption, or fix the many failures that exist.

These young people, who are capable of that, are mostly working in NGOs or teaching at universities, so they must be directed toward that. And unless the domestic private sector is energized, we will fail to attract foreign private capital into Ethiopia.

One example is that when a directive was issued saying foreign companies entering Ethiopia should only engage in trade, that was a mistake. The reason is that when these companies come to this country, they don’t only bring capital — they also bring work skills, administrative management, and above all, high-level connections and access to markets. They can export abroad. For example, if we say we will export roasted coffee or processed oil, it is very difficult for us to penetrate international markets. But those companies already have agreements in place.

So, they can open large markets for Ethiopia’s exports, and likewise, when they import, they have access to big markets. This means they can import high-quality inputs at low prices, which in turn can stimulate Ethiopia’s private sector. That is why I believe their role is essential.